A Trump appointee argues in dissent that OSHA’s workplace rules are unconstitutional

On Wednesday morning, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit issued what should have been a non-opinion.

A three-judge panel of the Republican appointees addressed what Judge Richard Griffin — a George W. Bush appointee to the appeals court — called a “simple but poignant challenge”: the question of “whether Congress’s delegation to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to set workplace-safety standards is constitutional.”

Noting the law’s history as having been signed into law by [Republican] Richard Nixon and having been “uniformly” upheld against challenges, the appeals court concluded, rather easily, that OSHA’s “delegation” is constitutional. Judge Deborah Cook, another George W. Bush appointee to the appeals court, joined Griffin’s 15-page opinion for the court.

Examining the arguments made by Allstates Refractory Contractors that OSHA violates the Constitution’s nondelegation doctrine, the appeals court concluded that “the Act comfortably falls within the ambit of delegations previously upheld by the Supreme Court.”

In short, the court concluded that the law and OSHA’s rules are fine.

The nondelegation doctrine addresses, at its most simple, the fact that Congress is the legislative branch and there are, at some point, limits on what elements of a “legislative” function it can delegate to other branches.

It’s a doctrine that sits on the outer edges of constitutional law, though, given that the last time it was used to strike down a federal provision the Supreme Court was fighting Franklin D. Roosevelt and New Deal legislation. Nonetheless, it is raised as an argument in litigation and has been given new attention by some conservatives in recent years — most notably by Justice Neil Gorsuch directly and in explaining what he views as the constitutional basis for the “major questions” doctrine.

In light of that, Wednesday’s ruling out of the Sixth Circuit did not end with Griffin’s 15 pages. Because it’s 2023 and because there was also a Trump appointee on the panel, Judge John Nalbandian, the court was not unanimous.

Nalbandian dissented, writing that “today” was the day to strike down OSHA.

Lest there be any doubt about Nalbandian’s view of himself and, well, all of the other judges, he began his dissent by suggesting that other judges have just been afraid to take the action he would have the court take:

For 88 years, federal courts have tiptoed around the idea that an act of Congress could be invalidated as an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power. The majority continues the trend. But, in my view, that streak should end today.

Nearly 30 pages later, Nalbandian concluded that, in his view, “OSHA violates Article I as an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power.”

In the pages in between, the appellate judge, who has been on the court since 2018, argued that the majority, the administration, and other courts to address the issue have it wrong. He also not-so-subtly urged the Supreme Court to take up the case and, perhaps, even change the entire test for looking at nondelegation challenges.

In depth

As the majority laid out the matter, the Supreme Court’s standard for addressing nondelegation challenges for nearly 100 years has been whether the law in question sets “an intelligible principle” directing the non-legislative entity as to what it is to do. That “intelligible principle” test is met, a more recent Supreme Court case cited by the majority detailed, “if Congress clearly delineates the general policy, the public agency which is to apply it, and the boundaries of this delegated authority.”

After reviewing the history of the test and the law, Griffin concluded for the court:

Congress has indeed laid out the general policy (a safe working environment), the agency to apply it (OSHA), and the boundaries of that authority (necessary standards to mitigate significant risks of harm).

Nalbandian argued that this is all wrong. He spent most of the dissent explaining how OSHA’s workplace safety rules are unconstitutional under the Supreme Court’s “intelligible principle” standard.

How does he do so? By heavy reliance on those two cases from the 1930s when the Supreme Court was fighting New Deal legislation.

He argues that the cases — Panama Refining v. Ryan and A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States — set up “two considerations” for nondelegation challenges: “(1) ‘whether the Congress has required any finding by the President in the exercise of the authority,’ and (2) ‘whether the Congress has set up a standard for the President’s action.’”

Notably, this tracks well with a piece that Mark Joseph Stern published on Tuesday about Trump judges’ reliance on “zombie precedents” — “old, repudiated decisions” that have not been formally overruled but, by their terms, cannot reflect any development of the law that followed them. His piece was about different decisions from Trump appointees — including the Eleventh Circuit’s Monday decision upholding Alabama’s ban on gender-affirming medical care for minors — but it is, yet again, relevant here.

As Griffin wrote in discussing the two 1930s nondelegation decisions, “[W]e must not read them in isolation, overlooking the many times that the Court upheld delegations of authority. … Instead, we must also follow the ‘broad leeway’ that Congress has under the Court’s entire nondelegation jurisprudence.” In any event, Griffin also concluded that OSHA is constitutional under Panama Refining and Schechter.

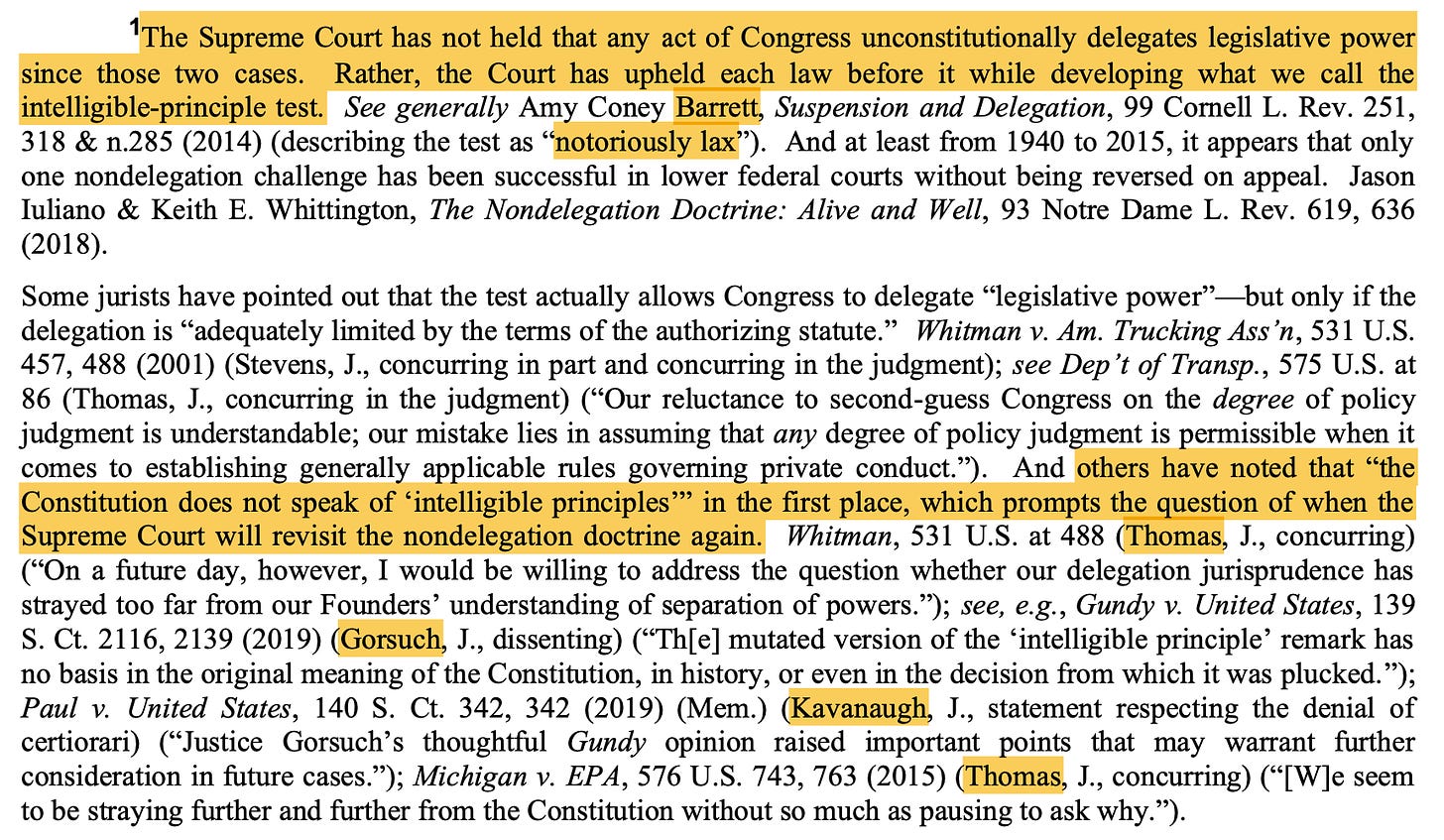

But, as noted earlier, Nalbandian doesn’t want this to be the end of this case and used footnotes to press his preferred path. In his first footnote, Nalbandian highlighted that several justices have, at least tentatively, suggested that the court could “revisit” the nondelegation doctrine.

He name-checks four current justices there — the number required for the Supreme Court to grant certiorari and hear a case.

Later, in case that subtlety was lost on someone, Nalbandian gets more direct. Not only does he think the Supreme Court should revisit the “intelligible principles” test, but he also gives his recommendation on what should replace it in footnote 17.

![17Though I believe that the Plaintiffs here ought to prevail under existing doctrine, were the Court to revisit how nondelegation under Article I operates, it ought to consider what Congress historically delegated to federal officials around the Framing. Some scholars have recognized that early delegations to the Executive are different from the delegations we typically see today. That’s because, before, the statutes authorized the executive to create rules that were only “binding” on executive officials, not members of the public. ... [scholars' quotes follow]] 17Though I believe that the Plaintiffs here ought to prevail under existing doctrine, were the Court to revisit how nondelegation under Article I operates, it ought to consider what Congress historically delegated to federal officials around the Framing. Some scholars have recognized that early delegations to the Executive are different from the delegations we typically see today. That’s because, before, the statutes authorized the executive to create rules that were only “binding” on executive officials, not members of the public. ... [scholars' quotes follow]]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fd9b3712c-6068-492e-9f29-a7e812690232_1706x604.png)

This is perhaps Nalbandian’s most radical act, a footnote that would dramatically curtail congressional delegation — and, by implication, most of the executive branch, insofar as the federal government takes actions against private actors (i.e., the public). Later in the footnote, he goes on to cite writings from both Gorsuch and Justice Clarence Thomas as evidence that “[s]ome Justices have already noted this issue.”

The bigger context

There is much discussion in conservative circles about “the administrative state” and how to pull it back, including at the Supreme Court. In this coming term, the Supreme Court has already agreed to hear a case addressing what is known as Chevron deference — a Supreme Court standard for when, in appropriate circumstances, an agency action is to be upheld — or, deferred to.

Nalbandian’s nondelegation dissent in Allstates goes much further because it addresses agencies only secondarily; it would, as its main effect, limit Congress.

Even this further-reaching argument did not come from nowhere. This is a case and argument being backed big-name conservative legal actors.

First, Allstates is represented by Jones Day. Specifically, the company’s lawyers include several former Trump administration lawyers — including former White House counsel Don McGahn. McGahn was White House counsel in the Trump administration throughout Nalbandian’s nomination and confirmation process to the appeals court. Other lawyers on the case include John Gore, who has a significant conservative record as the former acting head of the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department in the Trump administration, and Brett Shumate, who argued the case for Allstates at the Sixth Circuit and is another former Trump administration DOJ lawyer.

There also were significant amicus briefs arguing for Nalbandian to do exactly what he did on Wednesday. The Koch-backed Americans for Prosperity Foundation argued in an amicus brief in the Allstates case that “The Time Has Come to Enforce the Separation of Powers,“ as their brief put it in one section heading urging the appeals court to strike down OSHA’s rules. Regular Supreme Court litigator National Federation of Independent Business was on a brief lawyered by Mayer Brown, arguing that OSHA’s workplace safety rules are unconstitutional. The Pacific Legal Foundation also weighed in, perhaps most dramatically, arguing, that “if we apply OSHA’s toothless version of the intelligible principle test, we upset the social contract on which our republic stands.”

Given all that, expect an effort to get the full Sixth Circuit to review this case or the Supreme Court to take it up — or to get another case raising the question before the justices. (This, despite the fact that there are strong arguments against it, as put most strongly by the Justice Department, a multistate brief led by Illinois, and the Constitutional Accountability Center’s amici brief on behalf of law professors Julian Davis Mortenson and Nicholas Bagley.)

Trump appointees and today’s Supreme Court make this sort of big-scale, “nothing is off the table” approach our reality — even in a case in which two George W. Bush appeals court appointees considered and ultimately dismissed these arguments.